Peptide Sciences Research

Tesamorelin: Mechanisms and Emerging Applications in Metabolic and Longevity Medicine

Introduction: Age-Related Decline in Growth Hormone and the Rise of Visceral Adiposity

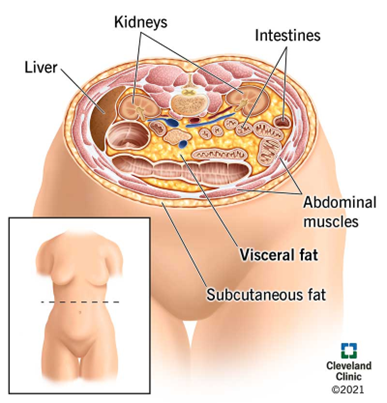

Endogenous growth hormone (GH) secretion steadily declines with advancing age, decreasing by approximately 15% per decade following early adulthood. This age-associated decline contributes to a range of physiological changes seen in middle-aged and older adults. Among the most prominent is the gradual but progressive accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), a metabolically active fat deposits located deep within the abdominal cavity surrounding vital organs.

VAT acts as an endocrine organ, secreting inflammatory cytokines, hormones, and adipokines that negatively impact metabolic homeostasis. Elevated VAT levels are strongly correlated with insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, systemic inflammation, and increased risk for cardiometabolic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular events. VAT accumulation also contributes to hepatic steatosis and may play a role in certain hormone-dependent cancers.

Unlike subcutaneous fat, which is relatively inert and located just beneath the skin, VAT is far more pathogenic. Recent population-based studies reveal that individuals with a normal body mass index (BMI) but high visceral fat exhibit disproportionately elevated risks of arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and all-cause mortality. These findings emphasize the limitations of BMI as a lone metric and highlight the importance of imaging-based assessments of fat distribution in assessing metabolic health and disease risk.

Biological Age vs. Chronological Age

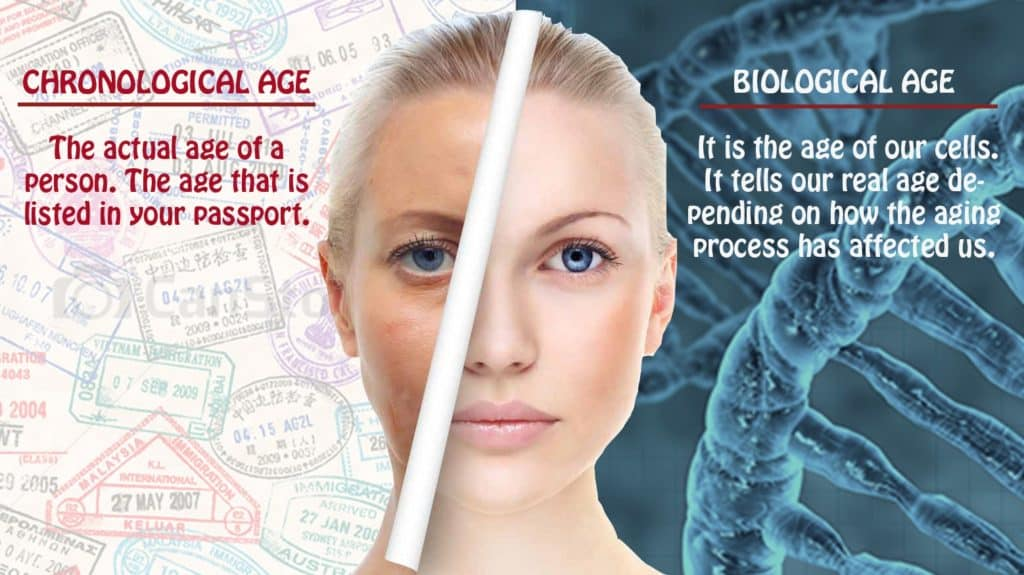

Chronological age is simple, it’s how many years you’ve been alive, based on your birth date. It’s the number you write on forms, used to qualify for a driver’s license or retirement benefits, and celebrated with birthday candles. But it tells us very little about the actual condition of your body. In contrast, biological age attempts to answer a more important question: how old are you really, in terms of health and cellular function? Biological age reflects how your body has aged due to lifestyle, genetics, environment, and stress, offering a more nuanced and actionable look at health.

Imagine two people who are both 50 years old. One has exercised regularly, eaten a whole-food diet, slept well, and managed stress effectively. The other has smoked, eaten poorly, and led a sedentary life. Despite sharing a birth year, their bodies may look and function very differently. The former might have the organs, skin, muscles, and brain function of someone 40; the latter might resemble someone closer to 60. That’s the difference between chronological and biological age.

Biological age is dynamic. While you can’t change when you are born, you can absolutely influence how your body ages. Things like poor sleep, processed food, pollution, chronic stress, and inactivity accelerate biological aging. On the flip side, healthy habits, especially those rooted in movement, nutrition, and recovery—can slow or even reverse signs of biological aging. Understanding this concept helps shift healthcare from reactive disease treatment to proactive wellness optimization.

In essence, your biological age is like your internal mileage. Two cars from 2005 could look very different under the hood based on how they were driven, maintained, and stored. Similarly, your biological age tells the story of how well your body has withstood the wear and tear of life, which is far more telling than your birth certificate.

Stem Cells vs. Exosomes: The Future of Regenerative Medicine

What Are Exosomes? Formation, Classification, and Cargo

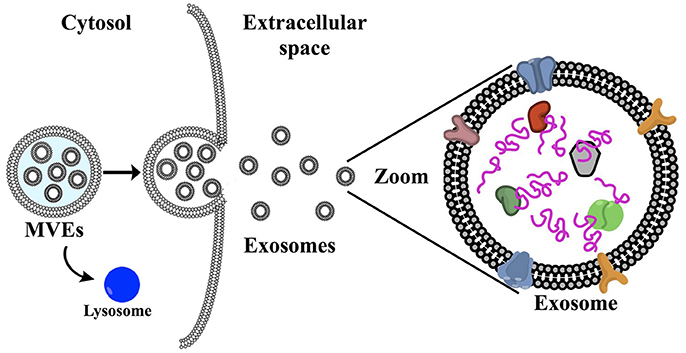

Exosomes are tiny membrane-bound vesicles (30–150 nm) released by virtually all cell types as part of their communication system. These vesicles originate from the inward budding of endosomal membranes, forming multivesicular bodies (MVBs) within the cell. When these MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane, they release the enclosed exosomes into the extracellular environment. This distinct biogenesis pathway sets exosomes apart from other extracellular vesicles, such as micro vesicles or apoptotic bodies, which form by outward budding or during cell death, respectively.

Once released, exosomes travel through bodily fluids like blood, saliva, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid, making them ideal candidates for non-invasive diagnostics. They function as biological messengers, transporting a complex mix of cargo that reflects the state and identity of their parent cell. Because of their stability and specificity, exosomes can deliver these messages to nearby or distant cells, where they are internalized and influence cellular behavior.

Their cargo includes:

- Proteins: These often include tetraspanins (like CD9, CD63, CD81), enzymes, and stress-response proteins such as heat shock proteins, which help maintain cellular function and communication.

- RNAs: Exosomes are rich in various RNA species, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), which regulate gene expression in recipient cells. They may also carry messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and other non-coding RNAs that play roles in epigenetic regulation.

- Lipids: Their membranes contain high levels of cholesterol, ceramides, and sphingolipids, which contribute to their structure, stability, and interaction with target cells.

- Other Molecules: Metabolites, signaling molecules, and even bits of DNA have been detected, suggesting a broad and dynamic role in intercellular signaling.

Exosomes act as precision couriers in the body, capable of transferring critical information from one cell to another. Their cargo and effects are influenced by the physiological or pathological state of the parent cell—meaning that exosomes from healthy cells differ significantly from those released by stressed or cancerous ones. This unique quality makes exosomes both powerful diagnostic tools and promising therapeutic agents, particularly in regenerative medicine, cancer therapy, and immune modulation.

PHDP5 Research for Alzheimer Disease

Introduction

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative condition that affects millions of people worldwide. However, treatments are available to help manage its symptoms, such as memory loss, confusion, and difficulties with thinking and reasoning. While these therapies do not stop the disease, some have shown promise in slowing its progression, offering hope for improving the quality of life for those affected.

Alzheimer’s is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of proteins in the brain, such as beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which interfere with the transmission of nerve impulses and disrupt normal brain function. These proteins build ups damage and ultimately kill brain cells, leading to the cognitive and functional decline associated with the disease.

In a groundbreaking study, researchers tested a synthetic peptide on mice genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. The findings were promising, showing that the treatment significantly reduced the buildup of these harmful proteins in the brain. Even more compelling, the peptide therapy appeared to restore key cognitive functions, such as memory and learning, which are typically impaired in Alzheimer’s patients.

This study written about below highlights the potential of innovative therapeutic approaches to target the root causes of Alzheimer’s, rather than just addressing its symptoms. While further research, including human trials, is necessary to validate these findings, this development represents a significant step forward in the quest for more effective treatments and, ultimately, a cure for Alzheimer’s disease.

The problem

As global life expectancy continues to rise, dementia has become an increasingly pressing public health challenge. The prevalence of dementia is projected to grow significantly, with studies estimating that over 150 million people worldwide could be affected by 2050. This staggering statistic underscores the urgent need for effective prevention and treatment strategies.

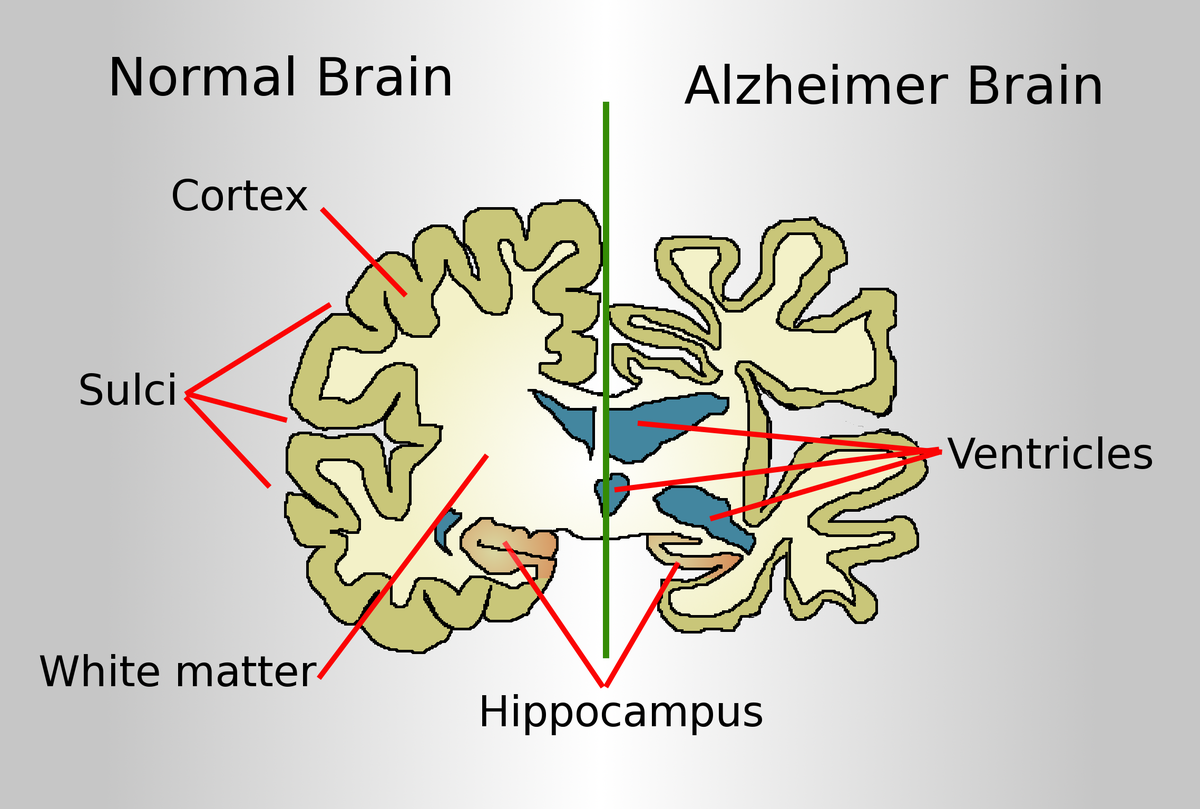

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is characterized by a variety of debilitating symptoms, including memory loss, cognitive decline, and personality changes. These symptoms are widely believed to result from the accumulation of two key proteins in the brain: beta-amyloid (Aβ) and tau. Beta-amyloid forms sticky plaques between neurons, while tau creates tangles within neurons, disrupting their structure and function. Together, these protein abnormalities lead to widespread neuronal damage, brain shrinkage, and the hallmark symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

Current treatments for Alzheimer’s primarily focus on alleviating symptoms, such as cognitive deficits and behavioral changes, rather than addressing the underlying causes of the disease. However, recent advancements have introduced disease-modifying therapies that aim to directly target these pathological proteins. For example, aducanumab and lecanemab, two monoclonal antibody treatments, have shown promise in reducing Aβ plaques in the brain. These therapies mark a significant step forward in targeting the disease at its root.

Despite these advancements, the use of monoclonal antibody treatments has sparked debate within the medical community. While they offer the potential to slow disease progression, their benefits are tempered by notable risks. Common side effects include brain swelling and microhemorrhages, raising concerns about the overall safety and efficacy of these treatments. Some experts question whether the modest clinical improvements observed in patients justify the associated risks, particularly considering the complex, multifactorial nature of Alzheimer’s disease.

As the global burden of dementia continues to rise, ongoing research is essential to refine these treatments, explore alternative therapeutic targets, and better understand the mechanisms underlying Alzheimer’s. The goal is to develop safer, more effective interventions that can not only slow disease progression but also prevent its onset, offering hope to millions of individuals and families affected by this devastating condition.

The Different Thymosin Beta-4 Fragments: What They Do and How They Differ

Introduction

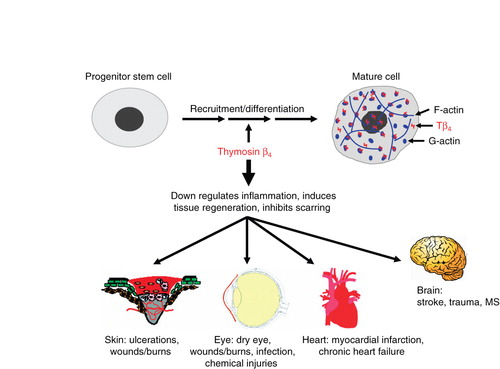

Thymosin Beta-4 (Tβ4) is a naturally occurring 43-amino acid peptide with a critical role in tissue repair, wound healing, inflammation modulation, and cellular protection. It is widely studied for its regenerative properties, particularly in cardiovascular health, neurology, ophthalmology, and dermatology. However, research has also identified several specific fragments of Tβ4, each exhibiting unique biological functions.

What is Thymosin Beta-4?

Thymosin is a hormone secreted from the thymus. The thymus is responsible for regulating the immune system and tissue repair. Thymosin Beta-4 has been found to play an important role in protection, regeneration, and remodeling of injured or damaged tissue. It is prescribed for acute injury, surgical repair, and patients that were once athletes that accumulated injury over their lifetime. It acts as a major actin-sequestering molecule and can be taken after cardiac injury for better healing of the tissue in the heart.